Story

When I’m not working on software, you’ll find me in aviation. I joined the Civil Air Patrol a few years back, where I was introduced to DAART, a new tool being furnished for government agencies to stream aerial imagery live. It was a pretty cool premise–the CAP pilot could be deployed to the site of a natural disaster very quickly and stream video to government officials thereby improving situational awareness and improving response times. When I got access to it, however, I quickly recognized its shortcomings.

The Discovery

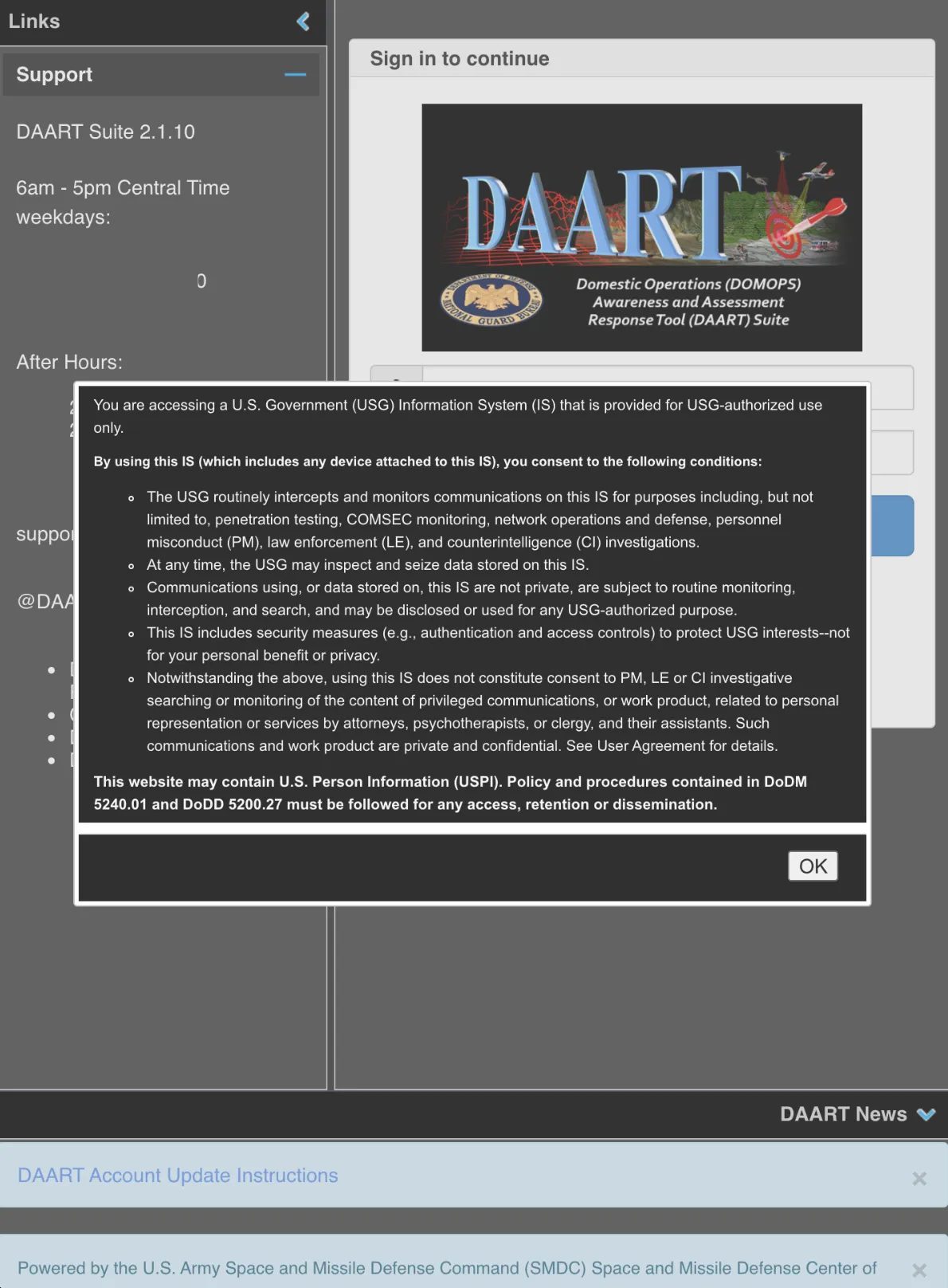

Instantly my spidey senses were tingling as I loaded the page. I sensed some real shortcuts taken by developers to get this product to market. For example, from a design perspective, I recognized Semantic UI, which had quickly fallen out of favor by 2022. I did not see a well-laid-out user experience either. The landing page contained all the menus and features you would need for the application. The screen had been split up into sidebars and footers, which could expand and collapse, reminiscent of forums of the early 2000s as opposed to minimalist, tabbed dashboards you might find in new SaaS products. I became skeptical of their capabilities as technologists.

Many developers acquire a sense of disdain for web products as they learn about the shortcuts one can take. Product managers push for vaporware. Startup CTOs insist on using their own superior design skills. Hurried developers forego careful planning. Testing is pushed aside.

I won’t belabor this point, but my mind rested on the pop up over the dashboard asking me to log in. If the log in modal exists over the unpopulated dashboard, that means the dashboard is ready for action. That means that dashboard might just be eagerly awaiting a boolean to say the user is logged in and can go get the data. That means then, that there might just be some routine that is one step away from revealing its secrets.

So I reached for the inspect tool. For the uninitiated, the inspect tool is found on basically all browsers. It reveals the underlying code that is sent to the browser. It presents in a digestible way what requests your browser is making, and what responses the server is sending. It’s pretty handy, and usually a right-click away.

Let’s see what requests it’s making before I log in, I thought. Maybe I’ll get some info about how they authenticate me, such as a session token or JWT. I tabbed over to network like I would hop in my car to go to work every day. And there, plain as day was a request called /getUsers. Well, hello there!

The Flaw

It turns out, that request is made every time the page loads. There is no payload and no magic parameters. In the real world, this might be like going to a hotel your friend reserved for you. Instead of asking for your name or even your friend’s name, the hotel hands you a list of today’s reservations and asks you to circle which one your friend is.

So I examined the response, and wow was I shocked. The hotel I went to was quite the open book, and teeming with feds. Here’s a sample:

{

"Total": 17123,

"Users": [

{

"LastName": "Rumsfeld",

"FirstName": "Donald",

"Email": "[email protected]"

}

]

}To return to my analogy, imagine if that reservation list was posted on the wall of the hotel under the portico like a menu at a walk-up restaurant. This GET request and its response was publicly available. There were indeed over 17 thousand records containing the emails and names of the people who used this tool. Since this was a government tool, and closely connected to the Air Force by way of the Civil Air Patrol, the majority of users had government emails.

Think about the ramifications of this public data. It’s a legal liability to expose this type of information, commonly referred to as Personally Identifiable Information, PII. Obviously any scammers who correlated this data with more info, like home addresses or phone numbers from other public databases, could create very targeted social engineering attacks. This dataset included military folks too. Our country uses complex and powerful encryption techniques to protect our communication, but humans tend to be the weakest piece of our armor. Identifying and retreiving credentials is a very common exploit, and an email list is a great start towards acquiring those credentials.

The website had a portentous message upon loading that forbade users from accessing this United States Government Information System. What a disgraceful sight to see that message in my browser and a publicly available query in the inspect window. I had to do something.

The Solution

It’s actually not too uncommon for technologists to come across bugs and vulnerabilities in web services. HackerOne furnishes a great pathway for those vulnerabilities to be reported. Many companies offer “bug bounties” via HackerOne to compensate those who find and report these vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities can cost the companies millions in legal fees, lost revenue, and even in ransoms, so it’s very worthwhile to offer a bounty program and reduce these problems.

In other words, of course I’m going to report this. I can protect my country and get compensated too!

At first, I attempted to call the company who built the app. The phone line did not work, which is surprising because it was listed as the help line. Then I emailed them and pointed out how trivial it was to extract their user base. I got nothing. I attempted to research them online, but for some reason, government contracting companies can be hard to investigate.

The United States Department of Defense does have a bug bounty program on HackerOne, so I reported my findings to them instead. I demonstrated the exploit. It was pretty easy, because I could just give them a URL to paste in the browser. It was something like domain.com/api/getusers?page=3&limit=20. A keen eye might also quickly see that limit is an adjustable parameter. Given that there was a Total in the response, one could abuse the server’s processing power and start a Denial of Service Attack.

The Bounty

Companies are notorious for not compensating security researchers for their findings. What would be a fair compensation for saving them from a class action lawsuit? Surely 1% of a class action would be sufficient. Or maybe a days worth of work for the security engineering manager who led the design. Perhaps the product is on a tight startup budget, so some swag would suffice (the most common).

For the work I had done protecting my country, I got the following response:

Greetings,

We have validated the vulnerability you reported and are preparing to forward this report to the affected DoD system owner for resolution. Thank you for bringing this vulnerability to our attention!

We will endeavor to answer any questions the system owners may have regarding this report; however, there is a possibility we will need to contact you if they require more information to resolve the vulnerability. You will receive another status update after we have confirmed your report has been resolved by the system owner. If you have any questions, please let me know. Thanks again for supporting the DoD Vulnerability Disclosure Program.

Regards,

The VDP Team

I was excited that the DoD had validated my finding! I have reported vulnerabilities before, but this one was more official, with a bug bounty program and more serious consequences. I anticipated the prize, or simply the fame for having found such an exploit!

The Reward

It wasn’t until a month later that I got a response. The DoD had some good news for me (their words), “the vulnerability [I] reported was resolved.” They also said thank you and, as a closing salutation, awarded me with “regards.”

And, yes, that URL started returning 401 codes, thus protecting the users who hadn’t been discovered yet.

The Cheese

If you used DAART, which was a stateside surveillance tool built recently for search and rescue and law enforcement, your email and name were public for the 1 day I used it and the 31 days following my report.

Maybe the moral of the story is pay top dollar for UX design to appear well thought out and robust.

Jokes aside, I’d like to use an aviation metaphor I learned in Civil Air Patrol, the Swiss Cheese Model. In short, organizations have multiple layers to prevent hazards so that no one person is responsible for letting something get by. For example, projects can include a planning phase to identify the needs and concerns of the product, or have a team of testers to constantly shore up weaknesses, or establish engineering practices to guard against vulnerabilities. Everyone plays a part mitigating risk, and every step identifies and mitigates some risk. If issues continue to happen it’s because those layers have too many holes.

And the other moral of the story is, kick the tires. If the tires are flat, maybe there are other problems too. This product was retired recently, and I can only speculate as to why. Nonetheless, it never hurts to take a quick look, and small squawks might lead to bigger problems elsewhere.